11 Lessons From Working On Tactile Sensors & What sort of tactile sensors do robot hands need anyway?

May 17, 2023

There are a lot of different views – and approaches – to making tactile sensors for robots, and quite a few books on the subject! Here at Shadow, we’ve made our own, we’ve worked with people making them, we’ve done collaborative projects around them and even got involved with PhDs around tactile sensor design. That’s taught us a few really interesting lessons that we’ve taken forwards in the design of tactile sensors for our robot hands.

- Materials matter.

It’s super important to remember that any touch sensor is going to be part of the contact material for grasping and interaction. So it will have to be robust and it will have to have the right sorts of stick-slip characteristics. Materials like silicones are likely to be your choice here – you can vary the hardness and cast them into shape for the robot. - The shape is critical.

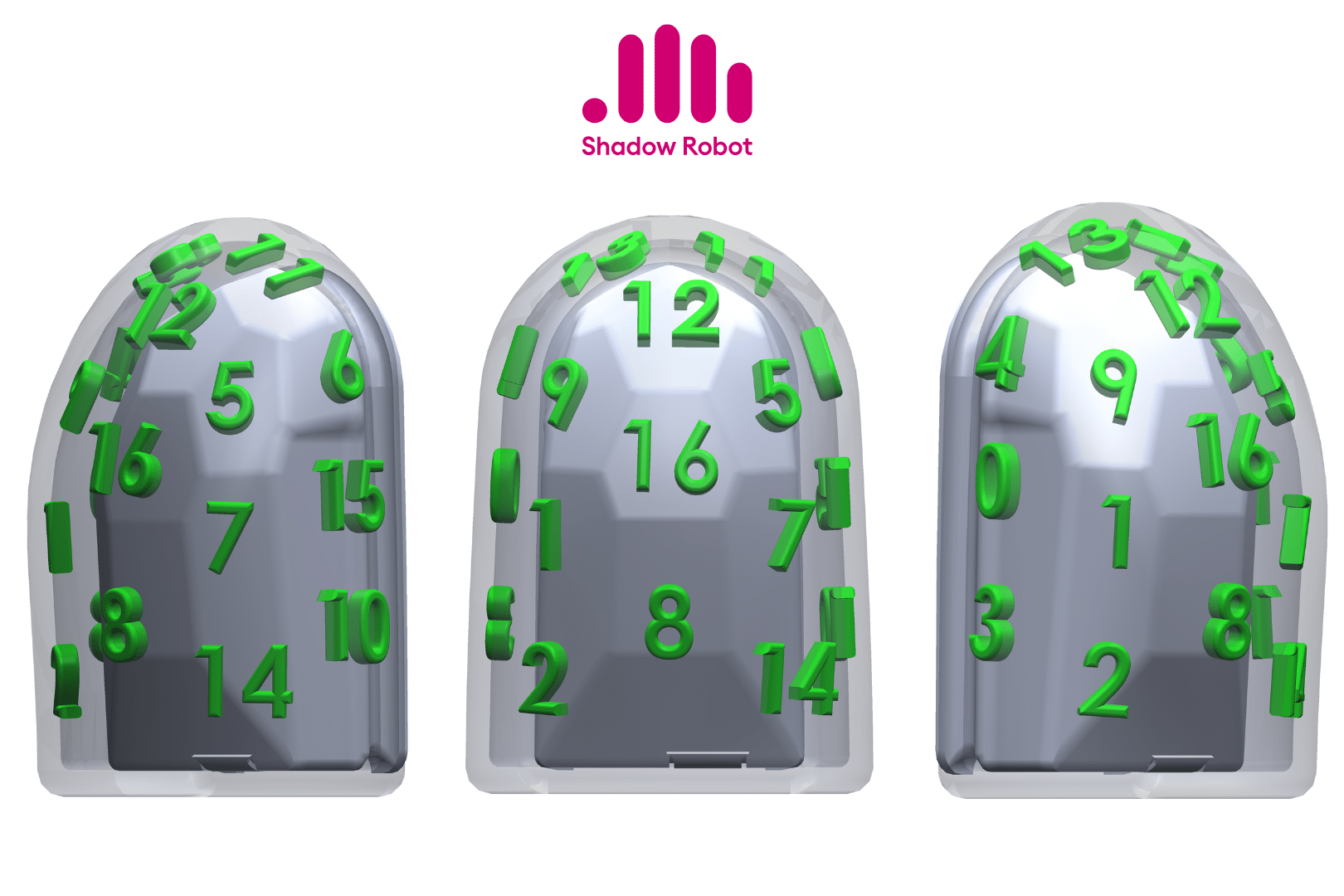

Robot hands are designed to have profiles that improve their ability to grasp and manipulate, and in our world most of these are curved – sometimes with complex curvatures! Flat sensors can be used in some places (a lot of the palm is flat – but not all of it) but if the sensor is to cope with the vagaries of the real world, the sensor is going to be curved. - Electronics & wiring.

We care a huge amount about the integration of electronics! A sensor material that performs really well on the bench, but needs a rack of sampling electronics to use it, just can’t fit on a robot hand. We’re often limited in terms of wiring to the sensor as well – we have 6 wires that go to the fingertip, for example – the sensor has to not only sample but also convert to digital for streaming. And do that in the small form factor of the fingertip… - We want the data to be stable.

Sensors that respond dynamically and not statically – so they give a reading on first contact but not on sustained pressure – are a real pain to use, because you have to remember the history of what’s happened! So we prefer sensors with static transducers to piezo elements, for example. But also we want the sensor to respond in the same way to the same contacts – to be reasonably repeatable. - It’s not all about quantity.

We need a lot of sensors in a small area – but not so many we can’t read them! We did a project once where the sensors were made at 100 micron pitch. Amazing sensors – but no way to get readout electronics on them! The discrimination distance for the human fingertip is a couple of mm – and that feels like the most dense sensor spacing we can use practically. - We want to read the sensor data out fast!

If a robot is moving at 1m/s then 1mm of travel takes 1 ms of time, so we need the sensor to respond right away! (OK, that’s probably too fast for most fingertip-touch applications, but I can hope…) We run our ros_control loop at 1kHz, so ideally the sensor would run that fast, although for practical reasons we settle at “at least 100Hz”. - The actual measured property is somewhere on our list!

We need to be measuring something useful for grasping and manipulation. At a minimum, that would be a local measurement of the interaction that’s taking place at that point. Sometimes vibration is helpful (BioTacs do this very well) and sometimes we want to measure the direction of the interaction as well as the magnitude. And this measurement has to take place over a lot of the surface of the hand or the finger – around those challenging curved surfaces and preferably in all directions – normal forces as well as shear forces and slip! - The sensing material needs to last!

The surface of the sensor is subject to abrasion (that’s what any sliding contact is, after all!) but the actual materials that convert from the applied contact into a signal need to keep working for days and days and days… We’ve seen materials (and we’ve built sensors!) that worked wonderfully in a lab test, but failed within 2 weeks in the field because they reacted badly with the real world – and that just isn’t acceptable! - Is the range wide enough?

Touch sensing has to handle light contacts of small objects as well as robots gripping with all their strength. There can be a thousand-fold variation in the forces at the two extremes – we don’t necessarily need to understand the top of the range in the same way as the bottom, but we do need that kind of spread. - What happens when we press it too hard?

Sure, the reading will saturate, and maybe it will take a little time to recover because a hard press is basically deformation, but will it recover? Is there an over-force point where the sensor just stops working and has to be repaired? Is that over-force point far closer to the operating range of the robot hand than you might like? We need headroom here – there’s always someone who wants to slam their robot hand into a wall or drop it on the floor. - Is it “Goldilocks squishy”?

A rigid robot surface won’t work for grasping because it can’t conform to the objects being grasped. And a really soft surface wears out quickly and becomes hard to understand how much squishing has happened. So you really want the squishiness to be “just right” – enough to make grasping work well but not so much that you lose precision. That’s a delicate balance of the material properties, and we have to be careful it doesn’t interfere with the performance of the sensed property.

One question we’re often asked is “How do you calibrate the sensor?” and – surprisingly – our answer to that is “we probably don’t”. If you want to measure the force a robot is applying with a tool, then you want a multi-axis force sensor, probably mounted in the wrist of the robot – and there are a load of companies that make those. But what we care about is the quality of the interaction – and usually, we can’t even apply a metric to that!

That’s a lot of constraints on the design space – which is why it’s so hard to get a sensor that satisfies everyone! Engineering is the art of dealing with constraints, and we have over the years found a few things that satisfied us enough on all of these dimensions.

If you want to get in touch with us or ask about our own tactile sensors (STF – Shadow Tactile Fingertips) drop us an email at hand@shadowrobot.com